|

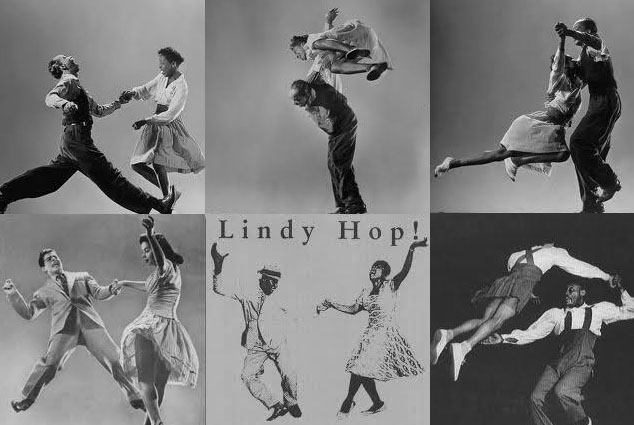

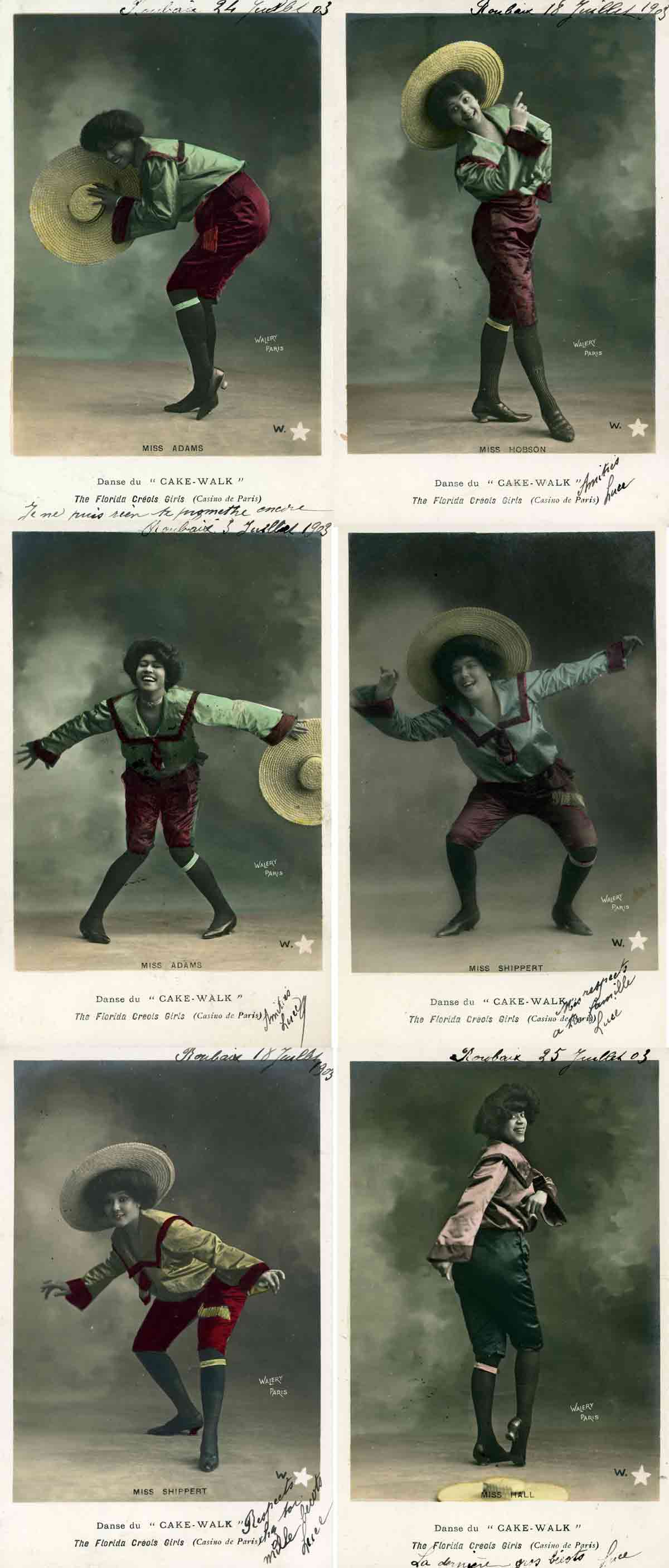

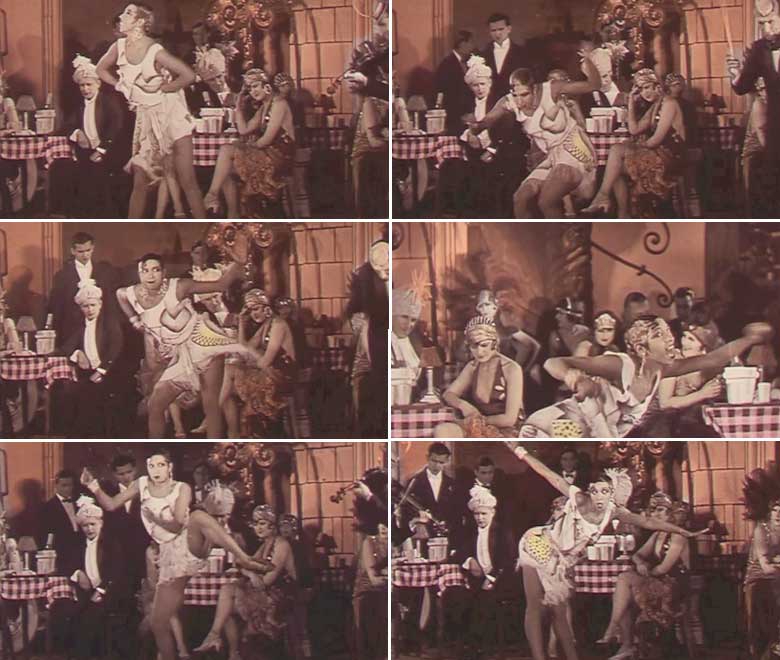

The Riddle of the Booty – Dancing and the Black Atlantic In 1943 African-American writer Ralph Ellison wrote: “Much in Negro life remains a mystery; perhaps the zoot suit conceals profound political meaning; perhaps the symmetrical frenzy of the Lindy-hop conceals clues to great potential powers–if only Negro leaders would solve this riddle.” InRace Rebels, a story about the everyday resistance of the African-American working class, the social historian Robin D. G. Kelley asks in retrospect why even Malcolm X could not solve this riddle. After all, he was wearing zoot suits himself and danced the Lindy Hop before he switched to the Nation of Islam and later became a major influence on Black Power in the 1960s. Kelley shows that a part of Malcolm X’s radicalism grew out of his experiences as a petty criminal and subproletarian dandy in Boston and New York in the 1940s, when he refused to be a good worker. But while Malcolm X danced, straightened his hair, and wore flamboyant outfits, the momentary freedom of dancing had no relation whatsoever to his everyday life: “In their efforts to escape and minimize exploitation, Malcolm and his homies became exploiters themselves,” is Kelley’s dry assessment.I Similarly contradictory images and situations are created by the dynamic of dancing today. From the zones of urban neglect around the Atlantic a “symmetrical madness” is reappearing that newly defines how bodies can move in public, beyond the limits of pain and feelings of shame. The bouncing booty shakes performed to electronic beats almost exceed the category of dance. The association with lap dancing is still one of the harmless varieties, in Dancehall one is sometimes struck with the impression that people are reproducing porn videos. Generally, women dancers act as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world to shake one's butt cheeks and massage a man’s genitals right in public. Videos of these scenes alternate between poised coolness and harrowing embarrassment. Mostly, however, the moves are cool because of their virtuosity. The jiggling butts have the beat totally under control; they’re just playing with it. Instead of the body reacting to the music, a peculiar co-existence emerges between movement and rhythm. A new level of virtuosity is reached, coming from a long history of a polemic of hips and butts. In the research on theRadical Riddims of the present and the new bass music, the talk has occasionally been of “dub virology”–the success and dissemination of this music is interpreted as a dynamic of contagion.II The viral metaphor attempts to describe effects of bodies and senses residing beneath the limit of consciousness. In fact, a particular form of communication takes place on the dance floor, mimetic, pantomimic, and wordless. But the metaphor of contagion moves within a discourse that has been debating social struggles as pathologies of the social body for more than a century. Instead of analyzing the political dimension of this communication in dancing, it implicitly propagates the myth of a dance fever. In the context of its emergence around 1900, this mythology insinuates that black dances from the Americas were foreign, came from the outside, and thus infected European bodies, whose immunities have been weakened by their dull everyday life. But the enigmatic explosive force of the dance of the Black Atlantic does not and did not lie in any abstract otherness, but in a concrete deviation from an all too familiar pattern. Blackness is not a virus, but an attitude, an embodied knowledge of historical experience.III Already our grandparents and great-grandparents participated in this knowledge production, on both sides of the Atlantic and on both sides of the Color Line. One line of origin for the current dynamic of dancing leads back to the time around 1900, when the first fashion dances created by the Black diaspora of the Americas became popular in Europe. Due to centuries of slave trade and colonialism, a space had emerged between the Americas, Europe, and Africa that was not charted on the territorial maps of nations and empires – the Black Atlantic. The dances that emerged from this context made relations of exploitation and resistance, of free and enforced labor, uprooting and redefinition spectacularly visible and newly negotiable. This can be seen particularly clearly in the Cakewalk, the first black popular dance from the Americas to find its way into European ballroom dancing around 1900.IV The Cakewalk was created under the conditions of slavery on the plantations of the American South. As a pantomimic promenade, it poked fun at European ballroom dancing, appropriating the elegance and prestige of the ruling class. Although not true to the original, but instead full of excess and exaggeration, it was always precise and virtuosic. The Cakewalk was not a dance with fixed steps, but a social situation that gave rise to competition. Improvisations were inserted into the stiff basis of the promenade, which created surprising and sometimes comedic effects, as can be seen in the film shown here. The prize at the plantations in the American South was apparently a cake, but around 1900 it shifted to money and luxury goods in the urban Cakewalk competitions. Everything in the Cakewalk was “shiny” and proper. Colorful, glittering material, inviting gestures, an unswerving stance. Two kinds of laughing are documented in oral histories about the Cakewalk: the laughing of the slaves and that of their masters, a liberating, self-reflexive laughter and a racist laughter that interpreted the performance of difference as failure to copy the original. “Sometimes the white folks noticed [our mockery], but they seemed to like it; I guess they thought we couldn't dance any better.”V There are many reasons why the Cakewalk became popular around the Atlantic around 1900. One reason was this divided laughter, which, even after slavery had been abolished, was still timely under the conditions of the racist division of labor, segregation, and discrimination. According to Roger Taylor, it was in this laughter that the cultural identity of the United States emerged. While African Americans mocked the idea of the white race, whites could distance themselves from European culture, which still set the norms of high society. With the help of black rhythms and dances, the body regime of European dance could be declared rigid, stiff, and out of date. “[In America] Europe is a fantasy, and in the fantasy Europe is debased and this is central to being American.” In this arrangement, black people should behave as whites, and in doing so to sufficiently exhibit that they were not, “revealing blackness through the white pose.” This doubled staging made blackness exploitable even for white Americans. The possibility of making fun of “uptight whiteness” under the mask of blackness produced the contagious effect of these cultural forms.VI This mechanism becomes particularly clear in the tradition of blackface in the minstrel shows, in which white actors painted their faces black and parodied African-American culture. Initially many minstrel shows were negotiating the borders of a free labor market under the mask of blackface, which weakened the explosive power of the social questions being treated in them.VII By 1900 this subproletarian form had solidified into a hypercommercial racist stereotype. African-Americans were allowed onto the stage and in film before a white audience only as laughing stocks, in order to perform the dumb country bumpkin or the recalcitrant dandy painted black. Other roles were not available. Around 1900 the success of the Cakewalk gave rise to a dynamic that broke this framework. In the minstrel shows it was only men who appeared. But the increasing demand for dances like the Cakewalk brought more and more women on stage. The first black musicals conquered Broadway. When the Cakewalk became popular in Europe as an American dance, the New York high society began to engage with the dance more seriously. The Cakewalk was a competition, and more and more spectators wanted to see “the real thing,” not the imitation of an imitation. The challenge lay in casually but spiritedly stepping into a stance that was actually awkward and in acting as if it was easy and natural. Something being a “Cakewalk” has remained an idiomatic phrase in American English to this day for an allegedly easy task. Under the influence of dances like the Cakewalk, heterosexual European couple dancing was irreversibly radicalized within a few decades. The popular dances that emerged over the course of this century had their origin in the history of slavery and the culture of resistance to racism among the black diaspora. They urbanized in the migration from the country into the cities, coming into contact there with the migration of the poor from Europe and a culture of dancing that equally challenged middle class norms. Since the traffic between New York, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, West Africa, and the European metropolises was accelerating in all directions around 1900, the new dances traveled just as quickly. Already around 1900 there was a transnationally networked world of commercial entertainment in circus, vaudeville, and variety shows, which was enormously mobile. Added to this were sex workers and their procurers fleeing from increasingly sharp attacks from governments and reform movements. The popular dances emerged precisely along the routes of these mobilities, all around the Atlantic, which simultaneously moved within the historical landscapes of Atlantic slavery and abolitionisms. The modern imperialism of the late nineteenth century violently sought to segregate this enormously complex situation along an imaginary color line. The Cakewalk made this situation visible in a new and unpredictable way and ridiculed the efforts to police such borders and boundaries. And with success: People that did not directly encounter one another, who did not speak the same language, and who also did not necessarily have any solidarity with each other’s problems took up the movements of the Cakewalk. The dance, equally beloved on both sides of the color line, produced an effective image of unpredictable change. The icon of the Cakewalk was a promenade danced with the hips forward. While the arms and legs go forward as if drawn by an invisible force, the head and torso lag strangely behind. It is no longer the head that leads the action, but the extremities, commanded by a new mobility of the hips. The Cakewalk itself was obviously not restricted to this figure. As can be seen from the short film clip, an entire repertoire of a dance techniques and dance polemics was already represented here, which has constantly been modernized and radicalized in popular dances, even up to the present day. This is particularly clear in the advertising postcards of the Florida Creole Girls, a troupe of African-American dancers who appeared on European stages around 1900. The third picture from the left seems to anticipate the Charleston of the 1920s. The Cakewalk was a ballroom dance, but it was also popular on the stage in vaudeville and the musical. This coincided with the invention of Modern Dance by dancers such as Mary Wigman and Isadora Duncan. They abolished the rigid corporal concept of ballet, dancing barefoot in flowing gowns. They were inspired by Greek antiquity and dreamed of a primitive and natural power of the body to create community. Yet, they distinguished themselves sharply from the experiments performed on the dance floor by their black and proletarian colleagues.VIII The dancers in the dance halls and on the vaudeville stages proceeded differently. They had no dreams of a natural body to be liberated so that it could govern itself better; instead of giving up the body to another regime of subjectivity, they used dance to analyze how such regimes worked in the first place. Instead of developing a new, presumably natural corporal regime, newly isolating the dancing body from everyday life, black popular dances profaned the smug superficiality of bourgeois subjectivity, the armored body, and the phantasm of interiority by showing that there was nothing concealed behind this surface: no secret, no intimacy, no treasure. Instead, the new dances enabled a new kind of surface, to make visible what had no name yet–the experience of a transformation impossible to control from any given position. This new use of the dancing body made no sense in reigning terms. It was crazy and profligate. Louis Feuillade’s 1909 short filmLa Bousse-Bousse-Mée makes fun of the possibility that the functional boundaries of bourgeois society could break down. A woman in the audience imitates a woman on stage, disturbing the subsequent course of the variety show, and is turned out of the theatre by the authorities. But outside, in the street, she continues dancing and the two policemen who had escorted her out take up her hip movements and start dancing themselves. The boundaries between stage and auditorium, between theatre and street, between private and public persona marked the difference of good society and demi-monde. Over the course of the nineteenth century, ever since the bourgeoisie excluded from its realm desires it could not fulfill within the boundaries of its norms and laws, the so-called demi-monde emerged, always close to the edge of sex work and intimately engaged with the urban economy of entertainment. This demi-monde stood in a polemical relationship to proper society, whose fashions and rituals it imitated and overstated. It expressed what was motivating people underneath their corsets and beer bellies, but what rarely could be put into words. The demi-monde was the avant-garde of fashion, its “pioneer,” as Georg Simmel put it at the time. Its “peculiarly uprooted form of life” gave it sufficient distance from social norms and enabled it to take a silent, unspoken lust for its destruction and put it into (aesthetic) practice.IX The focus of Feuillade’s parody of the danger of uncontrolled imitation through dancing are the female hips. In European fashion the hips and the behind of women had already been quite clearly marked by corsets and protruding skirts. Salome dances and veil dances confronted the audiences at vaudeville shows with the virtuosity of North African belly dancing, even before the advent of the Cakewalk. The popularity of the belly dance, much like the Cakewalk, marked the limits of colonial knowledge production and its mania for transforming people and things into objects that could be used or put to work at will. This becomes particularly clear in the history of the Hoochy Cooch. At the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, there wasWhite City and theMidway. InWhite City the great events of modern civilization were exhibited, technology and science. At theMidway a kind of global human zoo could be seen–at one end a West African village was constructed, at the other end a Scandinavian one. But world’s fairs did not simply illustrate the world, they organized it on a scale from primitive through traditional to the utopia of a technocratic modernity. Dance was a popular means on theMidway of presenting cultural difference vividly and entertainingly. But the spatial compression of the world in an exhibition and the particular dynamics of dance had unpredictable side effects. Somewhere in the middle of theMidway, between theAlgerian Palace and the mockup ofLittle Cairo, belly dancers from the Middle East appeared. The success of their performances was enormous. More visitors were interested in the Hoochy Cooch, as the Americans would soon call it, than in the latest technological inventions. But this was not uncalculated. 1893 was the beginning of an enormous economic crisis in the USA. The organizers of the fair turned to entertainment because they feared the fair would otherwise run in the red. The plan worked, but afterwards the USA would never get rid of this belly dance.X Soon, all over the US and Europe, women started appearing in vaudeville and variety shows, shaking their hips and doing belly dances. There were Salome dances, dances of veils, belly dances, transformation dances. Striptease, lap dance, and stripper dance follow in this tradition even today.XI When speaking of a virus, an epidemic, or a fever in the context of dances, rhythms, and movements of contagion, this discourse often negotiates a form of agency that emerges within existing divisions of time and space, yet was unintended or unplanned by its creators. The Salome dance on the stage made money, but Feuillade’s filmLa Bouss-Bouss-Mée also fantasized about such movements leaving this context and neutralizing a reigning regime of policing the borders of society. In the motif of contagion, however, such events were represented as a loss of race consciousness. Dancing like this was thus explained as a temporary state of emergency, a kind of childhood disease of modernity, which should be cured right away. In the way the police went after the inner city red light districts around 1900, when dance halls were closed and in part racially segregated, we can see that this was not just a matter of empty words. Much like bacteriologists with their microscopes, social scientists sought to find out what pathogens had afflicted the social body. They often observed dance floors because social relations and social problems were visible there in a peculiar way. Seldom, however, was this peculiarity related to struggles and polemics over such relations, but rather treated as representative of racial and cultural difference. In the nineteenth century, European scientists examined not only the heads and limbs of black and white people in order to pin down presumed racial differences in bodies, but they also examined women’s genitals, speculated about the meaning of the different sizes of labia, and differently shaped hips and buttocks. A favorite object of study was European sex workers and African women from the European colonies. The fact that so much attention was given in European culture to monitoring and restricting the movement of certain body parts cannot be attributed to any natural or culturally-conditioned feeling of shame. It stands in the tradition of racializing and pathologizing sex.XII In the rigid system of self-monitoring and self-control of nineteenth-century ballroom dancing, women were given particular responsibility. They were meant to foment desire on the dance floor like little flirt machines, yet not too much. Instead they were supposed to guarantee, through constant attentiveness, that the “social traffic,” as it was so charmingly called, ran according to course. With the discourse of contagion, this responsibility of individuals could more or less seriously be rejected. The myth of dance fever was thus not only repressive, it also made something possible–the dancers could give up responsibility for what went on. A popular narrative emerged, brought to a head here by Alice Guy, one of the first women filmmakers in film history, in her 1907 filmLe Piano Irresistible. In the Irresistible Piano, bourgeois city dwellers in their homes attempt to defend themselves against the music pressing in from outside. But against their own will their bodies make a different decision. In the end they all leave their individual apartments and start dancing around the piano through the new neighbor’s living room. Time and again these dancing bodies turn up in oblique positions. Legs and arms dance forward, while torsos and heads wonder what’s going on. Hips and butts thrust back and forth. The laughter in this film is self-reflexive–the dances of the Black Atlantic are present, but they do not produce any kind of racist laughter, they are not especially marked, but poke fun at modern life in general. The film negotiates the boundaries between stage and dance floor, between private and public space, between acceptable and embarrassing bodily movements. The laughter presents these boundaries as fleXIble. The dance movements animate the fantasy to expand these boundaries and make them livable. Change is presented as transformation, not as revolution. Shortly, however, a countermovement to the proliferation of these polemical gestures arose in Europe. Its most prominent agents were dance teachers. They had already almost become superfluous, since people started to teach each other the new dances on the dance floor. But not everybody could simply adjust to such new dance techniques. The division of the body into various centers of movement was complicated. If one wanted to dance in this way, one first had to learn how. But from whom? The dance teachers seized their chance and made themselves the new experts of “modern dances.” However, these modern dances, they claimed, were different from “negro dances.” “[The teaching of the Charleston] must restrict itself to the reduction and embellishment of exaggeration in athleticism, mimicry, and posing which might be very well among the black races but which have an absolutely horrendous effect among our amateurs.”XIII The self-appointed experts of the “modern dances” thus claimed that certain movements, positions, and gestures were appropriate “among the black races” but not amongst themselves and their students. In doing so they spoke in the name of the “white race,” invoking the category of racial consciousness. They ignored the polemic about this idea of the white race concentrated in such dances and instead explained it as a peculiarity of a foreign race. Thus, everything provocative, polemical, and anarchic in the dances could be projected again onto the presumably foreign culture. The society in ballroom dancing was white once again, and should remain that way. Experts invented a modern standard dance, which was meant to end the argument that had broken out about ballroom dancing once and for all. Against the endless variability of improvised body movements, they set up standard figures to newly moralize the dancing bodies. During her stay in Europe in the middle of the 1920s, Josephine Baker commented on this situation, when she claimed that the Europeans had seen the Charleston danced by African-Americans and invented another. “It’s not like the first one, but it’s also very pretty.” Nonetheless, one shouldn’t forget what the dance was actually about, namely, about “shaking your hips.” She didn’t understand why “the behind has become too hidden now.” It’s there after all and she also didn’t know what anyone had against it. There were some behinds, though, that still had a lot to learn. “But it is true that I know behinds that are so dumb, so pretentious, that the only thing they’re good for is to sit on them, and even that…”XIV The Charleston was soon followed by the Black Bottom, still in the 1920s. In the artificially linear narrative of dance fashions, which time and again newly hit Europe like natural disasters from outside, it was only logical that the tame Charleston would be followed by the shaking behinds of the Black Bottom, as a kind of revenge. Dance schools in the 1920 were also not the only place where the new dances could be learned. Josephine Baker often danced the night through in bars and clubs in Paris and Berlin after her performances. She writes: “Look at me, when I’m dancing in the middle of you–that’s how you have to dance. Not on stage, but in the middle of a group of people, clapping their hands and pressing ever closer, men and women, on the same level, in the same light, side by side.”XV In the 1920s Josephine Baker was in a complicated situation. Her success in Europe was unparalleled and set new standards in show business. But she could neither choose her roles herself nor fully control the staging of her appearances. Alongside arguments and conflicts behind the stage, Baker fokused on her own transformation, redefining the projections on herself as a potential for self-invention. “My manager thinks that I’m causing French women to change, and I think they’re changing me!”XVI Josephine Baker made fun of the desire that she produced, without acting it out or destroying it. She aroused it and laughingly channeled it in a new direction. She challenged the reigning morality of the body, but without celebrating anti-morality, as the Weimar art scene did, which at the same time was performing destructive scenes of cocaine-laden self-destruction. With Baker, everything was light and casual, ambiguous and difficult to pin down. She was present on stage, often almost entirely nude, without getting caught up in the guilt-laden and problematic relation of bourgeois society to the body in general and to the female body in particular. She shook this relation off herself, laughing it away, trampling it underfoot. In her work, dancing as well as writing, Josephine Baker allowed herself a laughter with which she sought to keep the world at bay, and to which she exposed herself so relentlessly. How difficult and painful this attitude could be in the long run is made clear by her posthumously published autobiography.XVII But in her early twenties, when she dictated her “memoirs” to the journalist Marcel Sauvage, she went on the offensive with every sentence, every gesture. “I can drive a carousel with my shoulders, I can play marbles with my eyes, I can snap like a crocodile, I can walk on my heels and I can walk on all fours if I want to, and then I can shake off every gaze.… In the end I’m no pin cushion…. With my hands, with my arms, I say who I am.”XVIII Baker eluded the question of her identity, her essence, her nature, which she constantly encountered as a black woman–with every movement, with every word. Her appearances on stage related to the situation she was living in–she related to a curious world that she had first encountered in her childhood as a threat.XIX Racist violence, neglect, abuse. Now that the whole world was crazy about her, she couldn’t take it very seriously. Her art and her convictions however, she was very serious about. As an artist she developed a distinct lightness. The history of popular dancing in the Black Atlantic is less a story of who the people were who danced so differently. It is more a story about dynamics of change they found themselves in, what made these dynamics possible, what restricted or violently prohibited them. Even the riddle of the booty in the present is easier to solve if we shift the question from representation to production. The question is not who we are when we dance this way, but what we can do by changing it. We have no terms, however, to describe this, no memory of our own history, only the perspectives and images of a history of the victor, which continually divides a shared historical context into old and new, black and white, revolution and reform. Although in this country, what prevailed was the gaze from the edge of the dance floor that problematized certain moves and gestures and relations, every new dance fashion staged polemics once again. The popping and locking booties of today are so provocative because they mobilize zones of the body still associated with the amalgamation of race and sex, and they do so with a virtuosity that was previously unknown. A regime of shame and silence, however, is not the expression of European culture, but the result of a specific history, which has it origins in colonialism and racism. In the last hundred years, a racist laughter was meant to bring in line again those who had gone astray in a more or less virtuosic way. In the resonances and reverberations of theBlack Atlantic, in which the Radical Riddims of the present emerge, we encounter a quite different history–a history of relationships, translations, and profaning laughter. Therefore, to conclude, a story from Africa, about the emergence of Kuduro in Angola. The name of this form of electronic dance music means “hard bottom.” As to the question of the term’s origin, the Angolan rapper and producer Tony Amado describes how he and his friends had seen the filmKickboxer with Jean Claude Van Damme at the beginning of the 1990s. In one scene, Van Damme dances to the poppy rhythm of a synthesizer, quite dramatically thrusting his hips back and forth. This hard bottom of Van Damme’s gave the new dance its name, according to Amado. The unceremonious gestures of the imitation of imitations shift the question of origin to a cultural and economic relation. Amado tells this story in answer to a question by the French musician and producer Frédéric Galliano, who had just then been introducing Kuduro in Europe.XX Galliano asks Amado where Kuduro comes from, and he tells a story not about Africa, nor about the breakdancing of his black brothers and sisters in the USA, but about the trashy video world of the 1980s. Amado’s story cuts short the angle of looking at Angola from the outside, positioning Kuduro in the tradition of theBlack Atlantic instead. The story updates the old polemic about dancing between blacks and whites, rejecting the demand for ethnic absolutism in the same move. Much like the case with the Cakewalk a hundred years ago, mute gestures and poses come into action precisely where it has proven to be not particularly successful to raise one’s voice and speak for oneself. Dancing enables communication of a different kind. It puts desires for change into action, puzzling movements, sometimes seductive, sometimes destructive, sometimes both at once. What happens next is history–which means the unpredictable and uncontrollable effects of power relations, strategies, and tactics, but also chance events and interferences between bodies, rhythms, light, and sound. Dance is therefore not resistant per se, on the contrary. But it has this special potential to challenge a reigning corporal regime. The dances of the Black Atlantic are excessive because they don’t invest in an economy of deferral. In the past they were able to interrupt the reigning division of bodies, times, and spaces of colonial modernity. What they can and will do in the present is still an open question. I Kelley, Robin D. G.:Race Rebels. Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class, II Steve Goodman,Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect and the Ecology of Fear, Cambridge 2010. III Cf. Thomas F. DeFrantz (ed.):Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, Madison/London 2002, 3-38. DeFrantz particularly criticizes the descriptive use of “black dance” as a synonym for African-American dance, while the term in fact should be used analytically, as a specific political concept in the tradition of the Black Power movement. IV Cf. Astrid Kusser: “Cakewalking the Anarchy of Empire,” in Volker Langbehn (ed.):German Colonialism, Visual Culture and Modern Memory, New York 2010, 87-104; idem: “Cakewalking.Fluchtlinien des Schwarzen Atlantik um 1900,” in idem/Ilka Becker/Michael Cuntz (eds.): Unmenge – Wie verteilt sich Handlungsmacht? Munich 2008, 251-282. In general on the heuristic model of the Black Atlantic, cf. Paul Gilroy:The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, Cambridge 1993. V The African-American actor Leigh Whipper is reproducing a conversation here that he had with his 80-year-old nurse. She describes how she had been brought to other plantations by the slaveholders in order to appear there with her partner in competitions with other slaves. Marshall Stearns/Jean Stearns:Jazz Dance. The Story of American Vernacular Dance [1968], New York 1994, 22. VI Roger L. Taylor: “Art: An Enemy of the People,” in David Meltzer (ed.):Reading Jazz, San Francisco: 1993, 123-137. VII Cf. W. T. Lhamon:Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop, Cambridge/London 1998. VIII Cf. Inge Baxmann: Mythos: Gemeinschaft. Körper- und Tanzkulturen in der Moderne, IX Georg Simmel: “Fashion,”The American Journal of Sociology, vol. LXII, May 1957, 541-58. X Cf. Lucinda Jarrett:Stripping in Time. A History of Erotic Dancing, London 1997; in general on the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, cf. C. Hinsley: “The world as marketplace: Commodification of the Exotic at the World’s Columbian Exhibition, Chicago 1893,” in Ivan Karp/Steven D. Lavine (eds.),Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, Washington DC 1991, XI The stripper dance of clowning also follows in this tradition. The dancers from South Central Los Angeles called their booty shakes by this name in David Lachappelle’s 2005 filmRize. XII Cf. Sonja Eismann: “Doin’ the Butt.Rassismen und Sexismen im Umgang mit dem afro-amerikanischen Frauenkörper in der Populärkultur,” in Testcard. Beiträge zur Popgeschichte 2004 13: 114-119; Sander L. Gilman: “Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature,” in Henry Louis Gates (ed.):Race, Writing and Difference, Chicago 1985, 223-261. Mieke Bal, however, justly criticizes the denunciatory gesture of this critique, which does not oppose the instrumentalization and objectification of women’s bodies, but instead performatively repeats it, cf. Mieke Bal:Double Exposure: The Subject of Cultural Analysis.New York 1996. XIII Moran, Paul: Moderne Tänze. Lehrbuch für Amateure, Vienna 1927/1928, 102. XIV Josephine Baker: Ich tue, was mir paßt. Vom Mississippi zu den Folies Bergère, Aufgeschrieben von Marcel Sauvage mit Zeichnungen von Paul Colin, Frankfurt am Main 1980 XV Baker, Ich tue, was mir paßt, 82. XVI Baker, Josephine: Ausgerechnet Bananen, Munich/Zurich 1978, 111. XVII Cf. Baker, Ausgerechnet Bananen. XVIII Baker, Ich tue, was mir paßt, 71. XIX Baker begins her autobiography succinctly: “My favorite childhood experience?…That’s a tough question. But I can tell you about some really terrible things. These memories I have always kept with me–unconsciously at first, then later very consciously. They have defined my life.” She is referring to a murderous attack by the white inhabitants of her hometown, St. Louis, Missouri, in 1917, on the city’s African-American community, followed by her first job with a white woman who physically abused her. Baker, Ausgerechnet Bananen, 13-16. XX Cf. Stefan Schulz: “Harte Beats für harte Hintern,” in Spiegel online, 20 February 2009, http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/musik/0,1518,608737,00.html (last viewed: 21 July 2010); “The Creation of Kuduru by Tony Amado, Interview mit Frédéric Galliano,” http://vids.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=vids.individual&videoid=2022901330

|

Erinnerung an vergangene Rätsel: Der Lindy Hop im visuellen Archiv der Google Bildersuche.

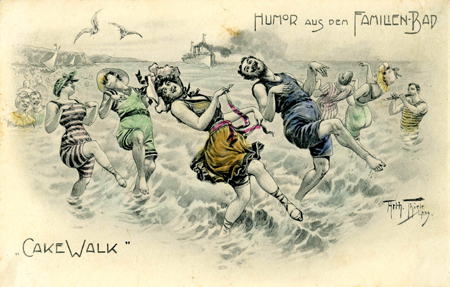

Die Rätsel gegenwärtiger Tanzdynamik: Der Booty Shake im globalen Dorf.  Cakewalk-Postkarte aus der digitalisierten Sammlung „Kolonialismus und afrikanische Diaspora auf Bildpostkarten“,Universitäts- und Staatsbibliothek Köln. Das Tanzpaar trat 1909 in Wien auf und verschickte diese Postkarte eigenhändig an befreundete Kollegen in Graz.

Comedy Cake Walk. American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, 1903. //hdl.loc.gov  Diese in Deutschland produzierte Postkarte wurde 1907 aus dem  Diese Serie von Bildpostkarten gaben die Florida Creole Girls 1902 in einem Pariser Fotostudio in Auftrag. Der Fotograf Lucien Walery entwickelte sich in den folgenden Jahrzehnten zu einem prominenten Fotografen von Varietétänzerinnen. In den 1920er Jahren machte er einige der noch heute berühmten Aufnahmen von Josephine Baker. Postkarte aus der digitalisierten Sammlung "Kolonialismus und afrikanische Diaspora auf Bildpostkarten", Universitäts- und Staatsbibliothek Köln

La Bousse-Bousse-Mée, Regie: Louis Feuillade, Frankreich 1909, in: Gaumont Studio. Le Cinema Premier, Frankreich 1897-1913, Regie: Alice Guy/Louis Feuillade/Léonce Perret [DVD 2008].

Le Piano Irresistible, Regie: Alice Guy, Frankreich 1907, in: Gaumont Studio.Le Cinema Premier, Frankreich 1897-1913, Regie: Alice Guy/LouisFeuillade/Léonce Perret [DVD 2008].

Mildred Melrose in: “The Real Black Bottom Dance”, British Pathé Newsreels,1927. //www.britishpathe.com

Josephine Baker, in: Die Königin der Revue, Regie: Joé Francys, Frankreich1927 [DVD 2005]. Es handelt sich um eine Szene aus der Revue La Foliedu Jour, Folies-Bergère, Paris 1926

Josephine Baker, in: Die Königin der Revue, Regie: Joé Francys, Frankreich1927 [DVD 2005]. Es handelt sich um eine Szene aus der Revue La Foliedu Jour, Folies-Bergère, Paris 1926.

Tony Amado erzählt Frédéric Galliano von der Entstehung von Kuduro in Angola in den 1980er Jahren. //www.myspace.com/video |