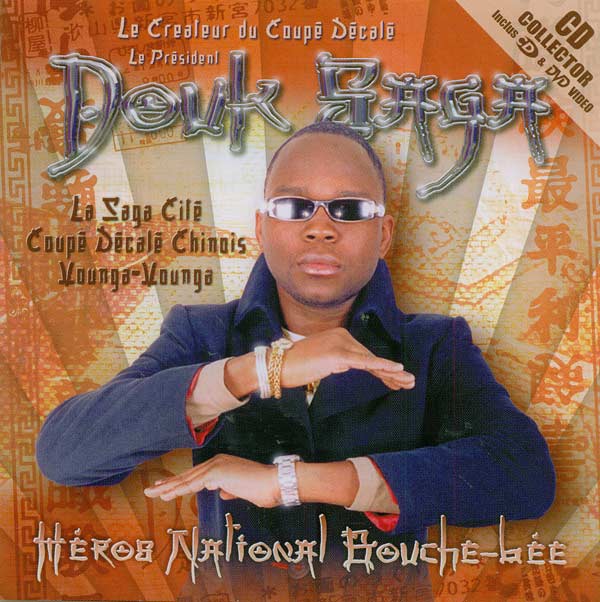

“CoupÉ DÉcalÉ – the Music of a New Generation Coupé-Decalé is currently perhaps the most popular music in Francophone Africa. It emerged in 2002 from a dance in the African nightclubs of Paris, which has become a symbol for a certain survival strategy among African (im)migrants in the diaspora. First the right hand makes a cut through the air: couper, French for cut. In nouchi, the youth slang of Abidjan, this means something like swiping or snatching away. Next comes a step backward, the hands reaching up and imitating the wings of an airplane: décaler, French for shifting or displacing. This means making off with the booty, for preference back home to Abidjan. Once there, the idea is to spend all the money on expensive luxury goods, designer clothes, expensive drinks, cigars, and handing out money at parties, which is called travailler, The hedonistic joie de vivre of travailler could also take on fairly grotesque forms. On April 17, 2004, the leading group La Jet Set, Douk Saga, who is considered the founding father of Coupé-Décalé, insinuated on the radio that he would be handing out money in the amount of around 3000 € to the visitors to his concert that night in the Club de la Culture. By the time he showed up that evening by motorboat at the banks of the laguna where the club was located, a large crowd had already gathered. He was holding a suitcase full of money in his hand, set off by a spotlight. When he entered the club the electricity suddenly went out; when the light was working again, guests and employees alike were asking what had become of the suitcase with the money… In this essay, among other things I would like to go on the lookout for Douk Saga’s suitcase. First I will look into the emergence of popular music in the Côte d’Ivoire, as well as into the musical aspects that Coupé-Décalé is based on. After this I will treat music and dances. In the third part I will examine the steps couper, décaler, and travailler individually, illuminating the social aspects and meanings that resonate with Coupé-Décalé. Abidjan – The Pearl of the Laguna After Côte d’Ivoire’s independence in 1960, the country’s economy flourished. Houphouët-Boigny, the first president and “Père de la Nation” had not entirely cut the ties to the former colonial power France, and the Côte d’Ivoire thus became a model example of capitalism in western Africa. Due to the political stability and relative lack of violence, the country, which was experiencing an economic boom in the founding years of the sixties and seventies, also became a (a) cultural center and pivot point. Musicians from all of western Africa swarmed into Abidjan to play concerts there and to have an album recorded in the modern sound studios. International record companies came to the country as well, building sound studios and production facilities, and establishing distribution networks for the music. The modern recording studios and record companies from Europe served as a magnet for many musicians in western and central Africa. Abidjan became the heart of the music industry and for many musicians was also the first step to an international career. Artists such as Salif Keita, Mory Kanté, Manu Dibango, or Amadou & Mariam traveled from Mali, Cameroon, or the Congo to record an album there. Alongside musical influences from the Congo, Highlife from Ghana, or Afrobeat from Nigeria, the first Ivorian pop music, Ziglibity, emerged in the seventies from the traditional rhythms of the Bété. It was the first step toward countering the dominant Congolese pop music with something native to the Côte d’Ivoire. Individual influences can still be found today in Coupé-Décalé. Crisis and Zouglou At the beginning of the eighties, the price dropped in the world market for cacao and coffee, the two most important export goods and the basis of the Ivorian economy. The resulting recession first hit the rural population, and then, over the course of the nineties, began to affect the inhabitants of the cities as well. The erstwhile economic miracle turned out to have been just a bubble. The crisis made urban life, which was always considered modern and progressive, more and more the privilege of a tiny elite. After Houphouët-Boigny’s death in 1993, who had economically mismanaged the country into ruin, students began to go onto the streets and fight for social and political equality. The frustration about the lack of perspective was musically reflected in Zouglou. Zouglou arose among the students in Yopougon, a district of Abidjan where student housing was located. Often there were fifteen students sharing one small room. “Be ti le zouglou” is Baoulé and means something like: “stacked up like on a trash heap”–it describes how they must have felt. After the Houphouët-Boigny era, there was a power struggle in the country. This sparked off hate and violence, which increasingly targeted migrants from other countries. The state ideology of Ivoirté gave the “real” Ivorians certain civic rights over other ethnic groups and was an instrument for disabling political opponents. There were Zouglou singers who expressed criticism in their music, but there were also patriotic Zouglou. But since, like reggae, which had come to the country in the eighties, it was protest music, it was often a thorn in the eye of the leaders. Due to the politically volatile situation in the country, many of Abidjan’s inhabitants left the country and went into exile toward the end of the nineties. This also included reggae artists, zouglou artists, and later Coupé-Décalé artists. Coupé-Décalé - La Jet Set Coupé Decalé originated in the nightclubs of Paris in early 2002. Members of the middle classes who could afford the trip to Europe or who had pieced together the money for a ticket by borrowing from the community turned up in the African nightclubs in Paris and began to make a name for themselves with their lavish behavior and extravagant outfits. They bought rounds of drinks and began handing money out to the guests at the clubs. In the beginning music was not the main factor, as in the case of the group Jet Set, the name for the group of friends around their leader Douk Saga. While he distributed bills among the guests, he was praised over the microphone by the atalaku, a mixture of African griot and party promoter. To show his gratitude, he performed his quite personal dance, the Coupé Décalé. Only later did he develop his own music in collaboration with DJs and the group Jet Set, which was only called Coupé Décalé after becoming popular in Abidjan. The dances remained the central element in Coupé Décalé. Each new song is also connected to a dance. The whole package is called a concept. By now there are well over a hundred of these concepts. New ones were added every week. The most well-known include Coupé Décalé, Petit Velo, Kpanpor, Coupé Décalé Chinois, Bobaraba, Équilibré, La Mastiboulance, and Drogbacité. In Petit Vélo the legs imitate the movement of a bicycle. The Drogbacité is performed by the Ivorian national football team when they have scored a goal. There is even a dance called the Décalé Allemand… It is striking how quickly the dances disseminate among the population and how capable they are of reacting to current events, which can be interspersed with the dances. DJ Lewis, for example, was personally presented with a medal by the agrarian minister of the Côte d’Ivoire. His album “Stop grippe aviaire” had drawn farmers’ attention to the impending pandemic. The dance Grippe Aviaire consists of floundering around on the ground as if in an attack of fever. The dances can also incorporate political themes. So, for instance, in the dance to the song Guantanamo by DJ Zidane, the hands are held together alternately in front of and behind the back–as if they were bound with handcuffs. When the group Jet Set moved back to Abidjan in 2003, the country had in fact broken into two parts. The army had rebelled in September of the previous year and was attempting to snatch power for themselves. The conflict worsened and the country landed on the verge of a civil war. Even when the conflict concerned the city of Abidjan, this had no negative effect on the popularity of the Coupé Décalé. The people were looking for distraction and locked themselves into the Maquis, the bars on the Rue Princess during the nightly curfew, dancing the whole night through to the Coupé Décalé. The music Coupé Décalé emerged out of the beats that the Ivorian DJs played in the clubs. These included many rhythms from Congolese pop music like Soukous, as it developed nearly pan-African popularity in the sixties. Coupé Décalé, just like Ziglibithy or Zouglou, can also be understood as a kind of counterproposal against the dominance of Congolese pop music. In the process, of course, many Congolese elements were newly interpreted and integrated. For example, with the atalaku it was originally a matter of an element of Congolese pop music. As we also know from dancehall, the atalaku intersperses names and prompts the audience to dance. He greets the people that come to the parties. In the interaction between the atalaku and the guest, the guest can celebrate his status. When Douk Saga showed up at the club, the atalaku usually had already announced him ahead of time, talking him up. For example, that he left 500 € in the club last time or that he wears the latest patent leather shoes from Weston, which cost 3000 €, that he parked his Mercedes Cabriolet outside and so forth. When he then entered the club, the people greeted him with cheers. He used this attention then to perform his dance and to hand out money–not only to the DJs and the atalaku, but also to the other visitors at the club. Couper – Golden Scissors There has been much speculation about where the group Jet Set’s money comes from. It is often said that they came to the money by fraudulent means. Common methods of the brouteurs, as con men are called in Abidjan, are, for instance, fake NGOs through which donations are acquired or cyberfraud, which in Nigeria is prevalent under the name 419, the paragraph in Nigerian law on “Advanced Fee Fraud.” This is a scam involving mass emails in which the receiver is offered sums in the millions. If he answers, there are constantly small problems in the way, which can seemingly be rectified by advancing small sums. Concerning the Coupé-Décalé artists, one often hears of bank card fraud; a middleman at the post office would take first the bank card and then the pin number from the post office…and so be able to empty the account. Another rumor has it that someone had managed to sell Abidjan’s national park Forêt du Banco to a sheik. Among African musicians, however, one often hears of visa trafficking, since for most people it is still relatively complicated to get a visa for Europe. The best-known example is the self-proclaimed king of the sapeurs and father of Congolese Rumba, Papa Wemba. In 2002 he was seized by the police in his apartment in Paris. Previously, there were arrests at Charles de Gaulle airport of 127 people who, on entering France, had claimed to be his musicians. Since there were so many of them, and none of them had any instruments of stage outfits with them, suspicions were raised and they were temporarily arrested. Later the police announced that those arrested were fishermen and goatherds from the Congo. Drug trafficking was also suspected time and again. Criminal fraud was the order of the day in Abidjan in the nineties. For the most part it was theft and receiving of stolen goods, for instance of mobile phones. The everyday presence and practice of fraud was also reflected in the large number of euphemisms: nouchi, the street slang, can itself be translated as bandit. Bizness became used as a synonym for the activities on the fringes of law. The cover of Solo Béton’s debut album, who had been a member of the group Jet Set, is adorned with a pair of large golden scissors, as a symbol for “Coupé” and the social acceptability of dubious money making schemes. Coupé here is juxtaposed with the respectable and in Abidjan very popular occupation of tailor. Coupé is not seen as immoral theft, but as something that someone from the edges of society is entitled to. Especially in the Côte d’Ivoire, it can often be seen as immoral if one does not share his possessions with friends and relatives. Couper in these cases can be an intervention that guarantees the cohesion of the group. Furthermore, couper can also make possible the fulfillment of individual consumerist cravings, for whoever comes to money unnoticed through couper can also secretly consume it all alone… Décaler – Staging Life as Jet Set (Live appearance by the group Jet Set on the television show “Tempo” on Côte d’Ivoire’s national broadcast station RTI) Back in Abidjan, the group Jet Set marches on stage in fine suits from European top designers like Dior, Dolce & Gabbana, Gucci, or Versace and crocodile shoes. Fashionable sunglasses are also part of the outfit as well as big cigars and purses from Louis Vuitton. They each also pulled trolley bags behind them. The bags contained a second outfit to change into during the show. Especially Douk Saga was known for having a second outfit for his show; the first one he threw out into the audience. Occasionally they would take rolls of cash from their pockets, which they would then hand out to the audience. This was all meant to create the impression that they were the new African jet set, arriving on stage directly from the business lounge at the airport. But what was really going on in the image? What was behind all of this? They played with the fascination and myth created by life in Paris, conspicuously staging their own wealth with music and the videos made for it. But it was not clear to everyone that this was purely about performance, and the jet sets were only artificial characters. The bluff was part of the success concept of the group Jet Set, above all in the early years. Often they only acted out the distribution of money, getting the money back from their friends after the show. It is said that Douk Saga often demanded double his fee so that he could pass out half of it on stage. But even for those in the know, it wasn’t important to call the bluff. For as long as the champagne was flowing, the designer clothes were real, and the bills that were being handed out during the travailler weren’t counterfeit – the music and its performance was perceived as good entertainment. There were also no attempts to find out how much money the artists really had in their bank accounts or what they really owned. The jet sets were so popular because they were examples of the good life, which apparently was possible after all. Travailler – Work in Two Senses The last and decisive step in the Coupé Décalé is the travailler – also called travaillement. Here public financial power is demonstratively converted into social competence through the distribution of money. The travaillement, however, is not to be understood ironically, but is really experienced as hard work. Here it is shown whether all the stresses and strains of the trip to Paris and back were actually worth it. In the travailler, two kinds of work are done: First, the appropriation of the whole know-how about modern consumerism is at the bottom of it, as well as the acquisition of expensive designer fashions and luxury articles. In this context one speaks of “travailler son apparance.” This is related to the sapeurs from the Congo, who used their expensive duds to create their own world of values and their own status system independent from the rest of society. They use travailler also to mean the time-consuming “making-yourself-chic” for the night of dancing ahead after returning from Paris. Distributing bank notes is also called "Travailler" meaning 'to work' because carrying the masses of money and throwing them around at the club is really refered to physical work/activity. "Travailler sur qn" figuratively means that there are suitcases full of money that are being unload on somebodies head. In Nigeria it is called "spraying of money" when musicians are being overwhelmed with bills worth thousands of euros at family celebrations and traditional weddings. The travailler, however, can also be understood as social work: to know who you have to work when and how, so that the social rise is legitimized and at the same time potential enviers are gotten out of the way. It is thus a matter of fulfilling one’s social obligations and solidarity, and paying back the travel costs for the trip to Europe, which were often arranged collectively. Traviller can also be examined in relation to sorcery. Even if it is not directly taken up in the music itself, it continues to play a large role in Ivorian society. So the new social climber, who does not behave in solidarity with his friends and relatives, can become the target of sorcery. Douk Saga himself, before his early death in the fall of 2006, blamed a friend for having cast a spell on him. Huge gifts of cash and demonstrative generosity can be seen as an effective means of pre-empting enviers – in Africa also always potential sorcerers – and also of justifying individual consumption of luxury items to one’s own community. The Akan have a famous saying: “If you do not allow your neighbor to have nine, you will not have ten.” One consequence of such a line of argument, however, is that it is only worth pursuing a regular job under certain conditions. If you were to just take it easy, you could always rely on your neighbor’s 'social debt'. Furthermore, this would explain the attraction of secretly amassing money through the couper. The image of a society in which property must be divided and to work seems senseless is reproduced in Coupé Décalé, and Douk Saga knew well how to use this stereotype to his advantage. He portrayed Ivorian society as full of envy, unable to grudge anyone individual success. By publicly distributing money, he stylized himself as an exception and a rescuer in need. Saying things like “L’ennemi de l’homme c’est l’homme” or “Les gens n’aiment pas les gens, mais ils aiment l’argent des gens,” he made no secret of his tactics. Even the title of his album made this black-and-white thinking clear: “Héros National Bouche-bée” (“National Hero mouth open”). “Si tu aimes la Jet Set applaudi!” What became of the suitcase full of money that went missing when the electricity went out at the Club de la Culture in Abidjan? Nobody could tell me the answer to that question. But we can run through three possible scenarios: The suitcase with the money was really stolen from Douk Saga, although this doesn’t necessarily mean that it was a theft, but perhaps a case of the “golden scissors” of couper, by which the society got back what was coming to it. Or it was sorcery that intervened here. More plausible is the third possible explanation. There was no money in the suitcase and it didn’t go missing. The theft and the electricity failure was just a bluff and part of the show. And it was a great success, for the story was the talk of the town in Abidjan for days afterward. And so the main actor really deserved the applause he got.

|

Douk Saga: „Saga en Fête“, Abidjan 2003  Solo Béton Album Cover Afrikanische Vorherrschaft: Selbst der Vater des kongolesischen Rumba's macht heute Coupé-Décalé Live-Auftritt der Gruppe Jet Set in der Fernsehshow “Tempo” des nationalen Fernsehsenders der Côte d'Ivoire RTI  DOUK SAGA Album Cover |